Greg Prince – My Journey

Posted on Feb 25, 2012 by Trevor in Religion

The following is a transcript I typed of a speech Greg Prince made at a Mormon Stories conference in Washington D.C. in October 2011. I’ve broken it down into five segments: Evolution and Diversity of Mormon Thought, My Own Journey, What I Have Learned from My Journey, What My Generation of Mormon Thinkers Has Accomplished, and What Remains for You to Do. This is the second segment, which runs from about 31:00 to 40:00 in the audio podcast, in which Prince gives the audience a brief overview of his own faith journey.

My Journey

I grew up in Los Angeles, a sixth-generation Mormon. Ours was one of the foundational families of Westwood Ward, whose chapel resides on the temple block. There was not a time during my childhood or youth when my father was not either a high counselor or member of the bishopric, and yet our family religious experience was one of orthopraxy rather than orthodoxy. My parents rarely discussed doctrinal or historical issues, perhaps because my maternal grandfather who resided in the same ward was a religious bigot whose fundamentalism regularly offended the masses and served as a strong counter-point to my later religious development.

After high school, I spent two years at Dixie College in St. George, Utah, prior to going on a mission. By packing the pre-dentistry curriculum into two years, averaging 19 credit hours per semester, I had little time for theology, although I attended church every Sunday.  I did not appreciate for many years thereafter the significance of the imprint that my next-door neighbor made on me. Her name was Juanita Brooks.

I did not appreciate for many years thereafter the significance of the imprint that my next-door neighbor made on me. Her name was Juanita Brooks.

Her husband, Will, then in his nineties, was our home teacher, and he never missed a month. I was young and dumb (as opposed to being old and dumb now), and even though I had some contact with Juanita, many years passed before I realized what a strong role model she was, combining a searing intellect, a steel backbone in the face of opposition from several apostles, and an immovable devotion to the church she loved in spite of the way its members dissed her.

One other thing happened while I was at Dixie, but its significance, like Juanita’s, would not become fully apparent for many years. Dialogue was born at Stanford University. More on that later.

I was conservative and unquestioning as a starry-eyed missionary in Brazil, but my understanding of Mormonism began to change there. Part of the change was a response to realities of the world—realities from which I had been sheltered at home and at Dixie, and part was the subtle influence of a nest of smart and somewhat dissident missionaries whose questioning caused me to question for the first time myself. A metaphor for the gradual shift in my philosophy was the fact that I took a copy of McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine to Brazil and left it there.

Within days of returning from my mission, I enrolled in the UCLA School of Dentistry. The year was 1969, (yes, there are people who were there who are still alive), a time of intense and sometimes violent ferment on campuses across the country, driven largely by the Vietnam war. The turbulence on campus was matched by that in UCLA Ward, where people sparred passionately—though never violently—as they argued conservative, liberal, and even heretical doctrinal positions in the classroom and at the pulpit. While I never experienced either an epiphany or a crisis of faith, I moved to the left.

While I was at UCLA, Dialogue moved from Stanford to UCLA. At one point I dated the Dialogue secretary, but my lasting relationship was not with her. It was [with] that woman on the stairs [he presumably gestures towards his wife]. Rather, it was at that point that I learned of and corresponded with Lester Bush, whose landmark monograph on blacks and Priesthood was moving through the editorial process towards publication. More on that later.

While I was embracing increasingly liberal religious thoughts, I was still in the mainstream of religious practice. I was called to be the regional president of the Latter-day Saint Student association, a position that on one occasion gave me direct access to Church president Harold B. Lee , and on another gave me an intense exposure to trickle-up revelation as I participated in the genesis of the Young Adult program as a local initiative, and then watched its rapid adoption by the central Church. A group meeting with a young apostle by the name of Monson was a memorable milestone in the process.

After six years of graduate school at UCLA, resulting in doctorate degrees in dentistry and pathology, I moved with JaLynn across the country to the National Institutes of Health. The initial appointment, as she will tell you to this day, was for two years, and the move was 36 years ago. I can’t count. We purchased a home in Gaithersburg Ward, having no idea that Lester Bush and his family had moved into the same ward one year previously. Lester became a mentor and my closest friend.

About a year after our move, the Equal Rights Amendment moved to the center of political discourse. We became acquainted with some of its highest profile LDS proponents, including Sonia Johnson, because Virginia was one of the last battleground states. Indeed, the ERA’s defeat in Virginia was its defeat nationally. Watching the all-male hierarchy square off against the all-female Mormons for ERA left a deep and permanent memory of the abuses that ecclesiastical power can spawn.

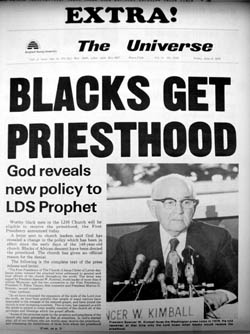

Three years after our move to Maryland, the Mormon world changed with Spencer Kimball’s revelation on Priesthood. JaLynn called me from the radio station where she was working and broke the news. We spent the evening at Lester’s home as dozens of phone calls poured in from across the country to congratulate him. We learned later that his monograph had been even more important in the process than we then realized.

Three years after our move to Maryland, the Mormon world changed with Spencer Kimball’s revelation on Priesthood. JaLynn called me from the radio station where she was working and broke the news. We spent the evening at Lester’s home as dozens of phone calls poured in from across the country to congratulate him. We learned later that his monograph had been even more important in the process than we then realized.

However, the whole episode turned out to be bittersweet, because I saw him become blacklisted by the church he had served so well. And, unlike Juanita Brooks who received similar treatment several decades earlier for her work on the Mountain Meadows Massacre, Lester eventually withdrew entirely from church activity. Even in the one true Church, it seems that no good deed goes unpunished.

My move to Maryland was followed by Dialogue’s move there. You see the theme? I couldn’t seem to escape it, even by moving across the country. Lester, who was the associate editor, pulled me firmly into the Dialogue orbit. My involvement has deepened since then, and I am currently in about my 15th year as a member of its board of directors.

My move to Maryland was followed by Dialogue’s move there. You see the theme? I couldn’t seem to escape it, even by moving across the country. Lester, who was the associate editor, pulled me firmly into the Dialogue orbit. My involvement has deepened since then, and I am currently in about my 15th year as a member of its board of directors.

One of the workers who showed up at Dialogue work meetings was Tony Hutchinson, a BYU graduate who was in a doctorate program in Biblical studies at Catholic University. For one memorable year, Lester, Tony, and I spent an evening together every week discussing at a deep level the most important doctrinal and historical issues facing Mormonism.

Lester and I received regular tutorials from Tony, who was perhaps the first Mormon to take the state-of-the-art tools of Biblical studies and apply them to Mormonism. His article, A Mormon Midrash, bumped around the Dialogue editorial office for five years before its editors, giving up on trying to edit something they didn’t understand, published it as-is. It is Tony’s most important contribution to Mormon scholarship, but few readers have the tools to understand its profound insights into the process of revelation. Maligned for his contributions, Tony eventually backed away from Mormonism and now is an ordained episcopalian priest. Their gain is our loss.

A year before the 1978 revelation, I was called as Elders Quorum president, a position I held for four years. Eager to do the job right, I began to study Priesthood intensely. I had a good LDS library then, perhaps 3,000 volumes, and I read everything that had been published on the subject, only to learn that most of the issues of interest to me had not been treated adequately by anybody. My study continued after I was released, and after several years of hoping that the real historians would give the topic the treatment it deserved, I had the audacity to decide to do it myself.

A year before the 1978 revelation, I was called as Elders Quorum president, a position I held for four years. Eager to do the job right, I began to study Priesthood intensely. I had a good LDS library then, perhaps 3,000 volumes, and I read everything that had been published on the subject, only to learn that most of the issues of interest to me had not been treated adequately by anybody. My study continued after I was released, and after several years of hoping that the real historians would give the topic the treatment it deserved, I had the audacity to decide to do it myself.

Using Lester Bush as my role model—he is a physician who had no training in historiography—I spent eight years researching LDS Priesthood and writing my book, Power from on High: The Development of Mormon Priesthood. Critically acclaimed, it nonetheless sent a shock wave through Church headquarters, and among other things, resulted in the longest article ever published by the Ensign, which restated orthodoxy while totally avoiding mention of my book.1 2 Power from on High led directly to the David O. McKay biography3, a project that occupied me for a full decade and opened my eyes widely to the innermost workings of the Church.

Footnotes

1Note: Representing the Joseph Smith Papers Project, Volume Co-editor Michael MacKay recently gave a presentation that I attended at Weber State University that was on the Restoration of the Melchizedek Priesthood. He referenced the Ensign article written by Larry Porter, labelling it the “sacred narrative”, but says that Porter now holds views on the process that are more in line with Greg Prince and the general understanding held by those researching and editing in the JSPP.

2In the Q&A session immediately following Greg’s speech (59:40 in the podcast), he was asked to elaborate on the effects his books on Priesthood and David McKay might have had on culture or curriculum. He said:

There was never any official response to either of the two books. I know that the Priesthood book sent some shock waves there. And the first real indication I had was Larry Porter’s article in the Ensign, and not long after that came out, I had dinner with one of the Seventies, who was pretty candid, and I said, “You know, it looks to me like that article was the Church’s attempt to say my book doesn’t exist.” And he laughed and said, “You’re a lot closer to the truth than you think.”

And I think the reason that it threatened them is that it retold the story in a different way than they were used to hearing. (If you read that book–and it’s not an easy read, I apologize for that, but there was nothing I could put that book on top of. I had to start with a new foundation because everybody else had looked at the data in the wrong way. They had missed. And what they had missed was a critical evaluation of when the accounts were written. That’s crucial. It’s not when they’re writing about, it’s when they were written, because everything is in flux. And you can’t make sense of it until you line them up chronologically that way. And when you do that, then it’s not a difficult story to tell.) But because of that, it told it in a very different way. You didn’t have the terms “the Melchizedek Priesthood” and “the Aaronic Priesthood” for six years. So why are you talking about the restoration of the Melchizedek Priesthood at all? It didn’t exist then. It was an earlier version that was much more rudimentary. And that’s what spooked them.

What I would have hoped would be the reaction—and I think maybe it was, for some of them who actually read it—was, “Hmm, this thing has always been fluid. And if it was fluid then, maybe it’s fluid now.” So it was in no sense an attempt to weaken their authority base. Actually, it turned out, I think, to strengthen it, because it says to them in a loud voice, if they want to listen to it, “Look, you guys are at the controls. All you need to do is put your foot back on the accelerator and drive this thing. And we’re here as passengers. You tell us where you want to go. We’re not trying to tell you. But the car is there and there’s gas in the tank. Just go for it.” That’s what that book should really say when it looks at the evolution of this whole thing.

3The McKay book—there have been interesting stories about that there has not been one negative word from anybody that I heard from directly and almost nothing indirectly. I know that it came before the Committee to Strengthen Members on at least two occasions, and the chairman of that committee told one of the other Seventies who told me, “You know, I’ve read that book. It’s a good book.” The ones who have read it understand it and like it. We were in Provo last week—JaLynn was honored by BYU as a distinguished alumna, an honor I will never get because I would be an alumnus instead of an alumna, and I didn’t go to BYU anyway—but we were talking with one of the Seventies who said, “I love your book.”

So, yeah, it’s doing much more than I had ever hoped that it would do. Are these changing things? I don’t know. Stick around. You never really know, because what’s the linkage in cause and effect? But the fact that a lot of people have read the McKay book—and they do read it, they read the whole thing, and then comment about it—says it was worth the ten years that I put into it.

Bill Kilpatrick

Jul 10th, 2013

I enjoyed reading this essay but wanted to tell you that the last paragraph should be stricken. It’s a repeat of the paragraph six paragraphs before it.

Trevor

Jul 16th, 2013

Thank you sir! Fixed 🙂