Greg Prince on Evolution and Diversity of Mormon Thought

Posted on Feb 25, 2012 by Trevor in Religion

The following is a transcript I typed of a speech Greg Prince made at a Mormon Stories conference in Washington D.C. in October 2011. I’ve broken it down into five segments: Evolution and Diversity of Mormon Thought, My Own Journey, What I Have Learned from My Journey, What My Generation of Mormon Thinkers Has Accomplished, and What Remains for You to Do. This is the first segment, which runs from about 20:00 to 31:00 in the audio podcast, in which Prince gives the audience a whirlwind tour through the highlights of changes in Mormon doctrine throughout its history.

Evolution and Diversity of Mormon Thought

Joseph Smith was the most progressive thinker of any LDS president. However, he was not defined by any standard label such as “liberal”, “conservative”, or “fundamentalist”. Rather, he was a creature of continual change, picking up and sometimes putting down symbols along the way as he constantly worked to translate his vision into something tangible enough that his flock could gain access to it.

Joseph Smith was the most progressive thinker of any LDS president. However, he was not defined by any standard label such as “liberal”, “conservative”, or “fundamentalist”. Rather, he was a creature of continual change, picking up and sometimes putting down symbols along the way as he constantly worked to translate his vision into something tangible enough that his flock could gain access to it.

The primacy of his thought and his leadership position, though occasionally challenged, was never overruled. By the time of his death, all of the basic elements of today’s LDS theology had at least been introduced. However, because his vision changed along the way, and because he was concerned about making the vision accessible rather than creating a tidy, systematic theology, he left behind an unruly patchwork theological quilt with which we have tinkered ever since, sometimes refining, sometimes discarding, rarely acknowledging the process openly.

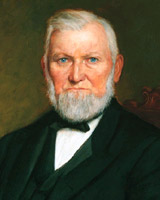

Brigham Young, the longest serving president, was a bold leader but not an intellectual. Much of his attention, and perhaps most of it, was devoted to practical exigencies rather than theological contemplation; for instance, the colonization and governance of the Great Basin, and then the quest for statehood, which came only after a half-century of intense struggle against the federal government and the American public, a struggle largely self inflicted by the public practice of polygamy, the solidification of a theocracy that presented a united front and an “in your face” attitude towards the larger country, and an occasional misstep, such as the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which dogged Young for the final two decades of his life. His most significant doctrinal forays led to two of the most controversial doctrines in our history, regarding both of which much of the Church is still in denial: Adam-God and blood atonement.

Brigham Young, the longest serving president, was a bold leader but not an intellectual. Much of his attention, and perhaps most of it, was devoted to practical exigencies rather than theological contemplation; for instance, the colonization and governance of the Great Basin, and then the quest for statehood, which came only after a half-century of intense struggle against the federal government and the American public, a struggle largely self inflicted by the public practice of polygamy, the solidification of a theocracy that presented a united front and an “in your face” attitude towards the larger country, and an occasional misstep, such as the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which dogged Young for the final two decades of his life. His most significant doctrinal forays led to two of the most controversial doctrines in our history, regarding both of which much of the Church is still in denial: Adam-God and blood atonement.

Meanwhile, the Pratt brothers [Parley P. and Orson] staked out doctrinal turf that was intellectually based and often threatening to Young. Ultimately the Pratts’ theology largely prevailed over Young’s, but along the way there was much doctrinal scuffling underneath the big tent.

John Taylor‘s ten-year term as president was spent mostly underground, as he attempted with little success to avoid the steadily closing jaws of federal pincers determined to crush polygamy, the remaining “relic of barbarism“. While he published a book on the Atonement and a pamphlet on Priesthood, both works served to restate positions of Joseph Smith rather than break new doctrinal ground.

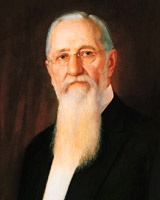

Wilford Woodruff‘s term, while spent above ground, was like Taylor’s—largely focused on preserving polygamy, and then in the face of overwhelming federal force, abandoning it in order to preserve the Church and obtain statehood for Utah. While Woodruff wrote no doctrinal works, he effected perhaps the most significant doctrinal development of the last half of the 19th century when, in response to a vision, he abolished the Law of Adoption (another doctrinal miscue by Brigham Young) and replaced it with the continuous sealing of child to parent for as many generations as genealogical research would allow. Ancestry.com owes its existence to Wilford Woodruff.

Wilford Woodruff‘s term, while spent above ground, was like Taylor’s—largely focused on preserving polygamy, and then in the face of overwhelming federal force, abandoning it in order to preserve the Church and obtain statehood for Utah. While Woodruff wrote no doctrinal works, he effected perhaps the most significant doctrinal development of the last half of the 19th century when, in response to a vision, he abolished the Law of Adoption (another doctrinal miscue by Brigham Young) and replaced it with the continuous sealing of child to parent for as many generations as genealogical research would allow. Ancestry.com owes its existence to Wilford Woodruff.

Lorenzo Snow, who served for only three years, reemphasized tithing, but added nothing of significance to Mormon thought while president. His earlier couplet, “As man is, God once was. As God is, man may become.” has been a mixed blessing. For while it emboldens Mormons, it undergirds the frequent charge by non-Mormons that we are a blasphemous religion. More on this later.

Joseph F. Smith, who served for 17 years, had a greater effect on LDS doctrine than any president since Joseph Smith. His efforts were largely in response to two major challenges to the Church.

Joseph F. Smith, who served for 17 years, had a greater effect on LDS doctrine than any president since Joseph Smith. His efforts were largely in response to two major challenges to the Church.

The first derived from the seating of Apostle Reed Smoot as United States senator. Smoot’s election in 1902 was a catalyst for pent-up anti-Mormon sentiment caused by aversion to the continuing secret practice of performing new plural marriages despite the 1890 Manifesto that was thought to have abolished it, and a persisting monolithic theocracy that seemed to elicit greater allegiance than the country in which it resided.

Hearings contesting the seating of Smoot lasted for three years, during which Smith was subpoenaed and had to testify before the Committee on Privileges and Elections. He was treated very harshly during the hearings, and shortly after returning to Salt Lake City, he issued a second manifesto that further disavowed the practice of polygamy while retaining it as a doctrine, and began to dissemble the theocracy and redefine some of the doctrines that had been the foundation of the Church since its beginning.

Part of that process was the transformation of Priesthood quorums into functional units, and for the first time, formal courses of study for them. The first, by B. H. Roberts, was the Seventies course in theology, a five-year challenging curriculum that is challenging even today to the reader, and perhaps enough so to Joseph F. Smith that it helped to shape his own doctrinal response.

The other challenge to Smith came in the form of the modernist heresy at the end of the century’s first decade. Based on higher criticism, another term for the increasingly scientific study of the Bible, it challenged many religious traditions as it discarded a dogmatic interpretation of scripture. Although still somewhat isolated geographically, Utah did not escape the heresy. Two sets of brothers teaching at Brigham Young University, the Petersons and the Chamberlins, were fired because of their embrace of higher criticism and organic evolution, and their liberal interpretation of Biblical and of LDS canon challenged the status quo. With Mormon orthodoxy under assault, Smith responded by writing and publishing a Melchizedek Priesthood manual, Gospel Doctrine, later published as a book that remains in print to this day. It defined and embedded a new orthodoxy, that while generally resonant with the teachings of Joseph Smith, pushed it towards fundamentalism, which was the common, knee-jerk reaction to modernism.

Smith’s successor, Heber J. Grant, was concerned about the Church’s position in the world rather than its doctrine, and neither he nor his successor, George Albert Smith, made any significant contributions to LDS doctrinal development. However, the selection by Joseph F. Smith of his son, Joseph Fielding , as an apostle in 1910, and the selection of Smith’s son-in-law Bruce McConkie as a General Authority in the 1940s, enabled fundamentalism to remain the predominant doctrinal philosophy within the Church to this day.

David O. McKay, while never directly engaging doctrinal issues during his 19 years as president, facilitated a counter-culture of doctrinal moderation by broadening the tent, preaching a gospel of tolerance and inclusion, and privately condemning McConkie’s book, this fostering indirectly the theological output of such moderate and liberal thinkers as Sterling McMurrin, Lowell Bennion, T. Edgar Lyon, Obert Tanner, Heber Snell, and Hugh Brown.

David O. McKay, while never directly engaging doctrinal issues during his 19 years as president, facilitated a counter-culture of doctrinal moderation by broadening the tent, preaching a gospel of tolerance and inclusion, and privately condemning McConkie’s book, this fostering indirectly the theological output of such moderate and liberal thinkers as Sterling McMurrin, Lowell Bennion, T. Edgar Lyon, Obert Tanner, Heber Snell, and Hugh Brown.

As Church presidents, Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold Lee, Spencer Kimball, Ezra Taft Benson, and Howard Hunter focused almost exclusively on pragmatic issues. Even Kimball, whose 1978 revelation on Priesthood transformed the Church, changed the policy without addressing its doctrinal implications. At the same time these presidents declined to break new doctrinal ground, Bruce McConkie, Boyd Packer, and a host of self-appointed, non-General Authority wannabes continued to push LDS doctrine in a fundamentalist direction. Alternative voices, most significant among them Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, were scorned or ignored by the orthodox, and yet managed to exert occasional influence far outweighing their continually shrinking subscription bases. (Dialogue [is] currently being subscribed by 1 in every 10,000 Latter-day Saints.)

A name I did not mention earlier, Gordon Hinckley, may have had more significance in LDS doctrinal development than we yet appreciate. Several years ago in a widely read interview with Richard Ostling first published in Time magazine and later in the book Mormon America, Hinckley’s response to Ostling’s question about the LDS doctrine of humans becoming gods shocked many church members. “I don’t know that we believe that,” he said. While Hinckley later told a group of concerned employees, “I think I know what we believe,” he never retracted his statement to Ostling, and thus left open the question of whether he was distancing the Church from yet another of Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo doctrines (think: polygamy), one that continues to be a wedge separating Mormonism from many other Christian churches. Stay tuned.

A name I did not mention earlier, Gordon Hinckley, may have had more significance in LDS doctrinal development than we yet appreciate. Several years ago in a widely read interview with Richard Ostling first published in Time magazine and later in the book Mormon America, Hinckley’s response to Ostling’s question about the LDS doctrine of humans becoming gods shocked many church members. “I don’t know that we believe that,” he said. While Hinckley later told a group of concerned employees, “I think I know what we believe,” he never retracted his statement to Ostling, and thus left open the question of whether he was distancing the Church from yet another of Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo doctrines (think: polygamy), one that continues to be a wedge separating Mormonism from many other Christian churches. Stay tuned.

The State of Mormon Theology Today

That, in a very small nutshell, is how we got to where we are today theologically. And where is that? Mormonism currently is a church that has never systematized its theology and indeed now teaches very little of it, or of its history, for that matter. Instead, our manuals and our sermons have increasingly focused on behavior rather than doctrine. While fundamentalism continues to be the predominant doctrinal philosophy of most Latter-day Saints, perhaps the most significant development of the past decade has been the gradual erasing of Bruce McConkie’s influence on doctrine. New church manuals either eliminate bibliographic references to McConkie quotes or eliminate the quotes entirely. Even more significant to the masses was the decision a year or so ago to take McConkie’s landmark book, Mormon Doctrine, out of print, a half-century after it was first published.

Will we continue to move in a direction of distancing ourselves from many of the doctrines that defined us for nearly two centuries? Will we move towards a more moderate doctrinal position than that staked out by McConkie and similar men? Again, stay tuned.

What Mormon Theology Looks Like | Times & Seasons

Jan 15th, 2013

[…] theology as part of his remarks to the Washington D.C. Mormon Stories Conference (as transcribed at this site): Mormonism currently is a church that has never systematized its theology and indeed now teaches […]

The Mo Hub | Prince on the Evolution of Mormon Thought

Mar 4th, 2013

[…] stumbled across a Greg Prince talk giving a nice overview of Mormon thought in the past and present. It's not an approach one […]

Obedience and Cherry-Picking | Common Sense for Latter-Day Saints

Aug 4th, 2013

[…] Rather than pursuing such a course, the Church has Instead perpetuated certain rules that are thought to be infallible despite the fact that there may be overwhelming evidence against them. Rules such as the current mangled-up version of the Word of Wisdom, which is unrecognizably different from D&C 89. Abstinence before marriage may be healthy, but instead we are teaching that if a mistake is made and our powerful instincts get the better of us we are irreparably damaged. These and many other teachings and practices may have been well-intentioned at first, but they have since grown into dogma that the Church would rather stubbornly protect despite the immense collateral damage done by doing so, rather than simply accepting that some rethinking would be the smart thing to do. This is cherry-picking. Certain parts of the Bible, of other scripture, and even of early Church leaders are accepted and promoted today because they conveniently fit into the mold that leaders have created. The rest is ignored. We are taught to apply the scriptures to ourselves, which means that we should consider each verse and what it truly means when applied to our current state. Instead, we cherry-pick, often paying a hefty price and losing many of our best by doing so (see this link). […]